|

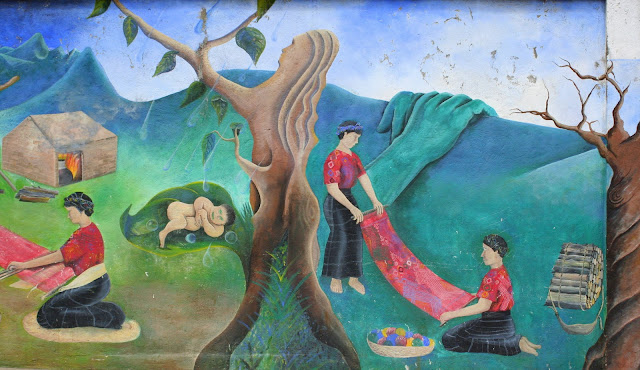

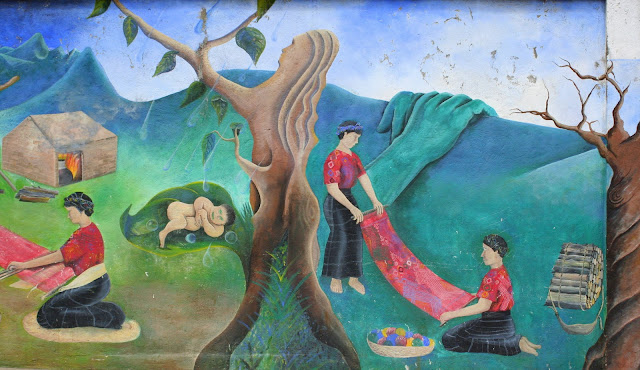

| Nuestra Madre Tierra - Mural in the center of town |

I began planning my trip to Guatemala more than a year ago when I became restless with my job. I contacted many organizations and clinics, including Primeros Pasos, Midwives for Midwives, and XelaAid. In 2005 I met a Peace Corps volunteer who told me that he was working with midwives in San Martin. He promised to tell them about my interest in working with them. We kept in touch through email and I later received a message stating that they had extended an invitation for me to come work and stay with them. Unfortunately, the email came just two days before I was leaving the country. And that was that.

The day I met the ACAM midwives was a fortunate one. My XelaAid contact, Luis Enrique de Leon, director of the clinic in San Martin, drove me to Concepcion Chiquirichapa. He had given them no warning and when we arrived they were busy with a patient who needed an ultrasound, to confirm that one of her twins did not die in the womb. The clinic only has bare minimum supplies. After the business of getting her seen in San Martin, Luis and I sat down with Dona Azucena, President of ACAM and Dona Antonina, Vice President. We talked for a while and I laid out my goals for working with them and offered them to come up with a list of projects they need assistance with. So they agreed to have me and offered a place to stay and homecooked meals. And on my first night here I assisted with my first birth, whose story I talk about at the end.

|

| Where I live |

|

| La Iglesia Catolica - View from ACAM |

|

| Technicolor Cemetery |

I've been here now since the beginning of March and am just now blogging. With my computer out of commission and their computer's internet very spotty, I'm typing this on Matt's Kindle. Crazy. I am living in Barrio Nuevo, Concepcion Chiquirichapa, a small pueblo about 30 minutes from the city. This is where the clinic is located. Here life is rich with culture, color, and community and so has been my experience living in this traditional Mam Mayan town.

|

| La Casa de Comadronas |

|

| Examination Room |

ACAM is the Association of Comadronas in the Area Mam. The clinic is a beautiful house that hosts Computer classes, English classes, community meetings, patient consults (prenatal, postnatal, and general) and of course, births. I teach the comadronas English when there is a short moment to do so and even taught one girl Algebra since no one here was able to help. Teaching Algebra in Spanish isnt easy. Two weeks ago we hosted a large meeting of women's groups from all over the region on el Dia de las Mujeres -- when three visiting American professors led a discussion about the problems the women see in the local environment and offered ideas on how to protect their precious Madre Tierra. These groups are a means to empower women to effect change in their communities. You can see how this place is special.

|

| La Hermosa Comadrona Santos |

|

| Comadrona Ofelia examines a patient |

The consult room is very simple. There is also a small closet full of donated medicines...our pharmacy, a waiting room, three birthing rooms, a kitchen, a medicinal herbs cabinet, the large salon where meetings are held, computer room, office, five bathrooms, the midwives bedroom (they rotate staying 24 hours, two at a time), and three more bedrooms for visiting guests like myself. And even the traditional sauna called temazcal, or in Mam, chuj, in which some moms enter while in labor or after childbirth.

I began seeing consults immediately with Antonina who quickly became my favorite and to whom I refer now as my Mayan Mama. She insisted immediately that I examine the prenatal patients and tell her my impression. Since I have no experience in checking the baby's position, I mostly pretended and was self-assured with my touch, palpating the baby's head (I was at least able to do that...most of the time), checking the baby's heartrate with a fetoscope or doppler, then checking her blood pressure and her weight. Antonina continues to offer tips on how to be more attuned to how the baby feels in utero but I continue to have trouble sensing where his or her arms and legs are.

|

| Mi paseo |

The pace is slow here and the days are tranquil. Before my computer died I spent my nights

watching an episode or two of Grey.s Anatomy (Yes. Greys Anatomy) or a bootlegged copy of American movies I bought at the market in Xela. Now I am left with playing Scrabble on this Kindle. And I just finished reading for the second time (Yes...I read something in its entirety) The Red Tent, which fictionalizes the biblical life of a midwife, Dinah, daughter of Jacob. I loved it this time too. I've also made it a routine of mine to go on walks-hikes around the community and up into the hills. But when I'm really lucky, a birth keeps us occupied at night...and this was the case my first night living in Concepcion.

|

| Mercado en el Centro de Concepcion |

Luisa's Childbirth

Dona Antonina looking at me plainly and sternly said "Come closer Dana. You're going to catch the baby." I sort of looked at her blankly and hesitated to step forward. To this she challenged me with "What's wrong, are you scared?" I stepped up to the woman's side and held the fleece blanket in my hands. But even as the head of hair began bulging I wondered if maybe she misunderstood my birth assisting experience and I stood dumbfounded. The baby's head came first. Antonina had no time to entertain my awkwardness so she reached for the baby and with a swift lateral pass the baby was in my arms. Receiving a newborn in this context, in the house of midwives, is unlike receiving a baby when I worked in the NICU -- where tension, anxiety, and fear hangs in the air. Here the healthy newborn was wide-eyed and the thick ropy pulsing cord that sustained him in his mama's womb was still attached. After a few moments I was instructed to care for the cord; tie it, clamp it, cut it, and then he was free and making his own way. I wiped the baby, caked in vernix and blood, to encourage the familiar lusty cry that signals new life. Antonina assumed reponsibility of caring for the baby while I was tasked with helping the mom birth the placenta. I stood at the woman's side massaging her uterus with my left hand and holding the cut umbilical cord with my right. The intact placenta didnt need a lot of coaxing and in seconds mom was free of it. She sunk into the pillow in exhaustion.

It all happened quickly and it was incredibly exciting for me -- like an initiation into the world of babycatching. I remember thinking- I think I'll like it here.

|

| A large Batik that hangs in the Clinic |